|

Rampart Records’ founder had hoped it would become a ‘Mexican American Motown.’ Its current head just hopes it can keep on going.

January 08, 2013| By Hector Becerra, Los Angeles Times

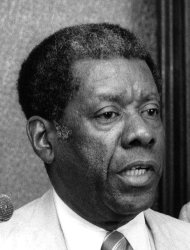

Hector Gonzalez earlier had a career as a TV sound-man, receiving an Emmy award as part of a team covering the 1984 Olympics. He took a buyout from CBS after the Rampart Records founder died and left the business to him in 1994.

Hector Gonzalez earlier had a career as a TV sound-man, receiving an Emmy… (Irfan Khan / Los Angeles…)

Hector Gonzalez straps a five-string bass guitar over his belly inside a music studio on a dreary stretch of Monterey Park. He plays as a smooth, prerecorded tenor joins a funky accordion through his headphones.

Trying to bite a bullet, or sometimes count to 10,

For the sake of argument, let’s just pretend,

We both agree to disagree.

Gonzalez is helping a silky-voiced old band-mate record a nostalgic-sounding soul album. But in a larger sense, the 59-year-old music producer is trying to keep alive a legacy he inherited 18 years ago.

Gonzalez is the head of Rampart Records, which earned a measure of fame in the 1960s as the originator of the “West Coast East-side Sound” — and whose founder dreamed of its becoming a Mexican American Motown.

That was Eddie Davis, who produced bands from Boyle Heights, East L.A. and the San Gabriel Valley with names like the Blendells, the Romancers, the Premiers, and Cannibal and the Headhunters. The last group toured with the Beatles in 1965 after scoring a big hit with “Land of a Thousand Dances.”

Rampart’s stable of musicians consisted of kids from the barrios, often discouraged by their parents from speaking Spanish because they were afraid they would be discriminated against. Their role models were often black artists. One weekend they might share the same stage at the El Monte Legion Stadium with Chuck Berry or Ray Charles, and the next vie with mariachis for gigs at baptismal parties, quinceañeras and weddings.

But by the 1970s, with immigration from Mexico booming, the distinctly Mexican American sound that Rampart championed — almost all of it sung in English — became overshadowed by Mexican music, which appealed to both the American-born and the immigrant.

Even though several Mexican American bands, including East L.A.’s Los Lobos, have gained fame since, Gonzalez believes most acts are largely overshadowed by Spanish-language artists, particularly from Mexico, who get to tap into a colossal media network including TV giants like Univision and popular Spanish-language radio stations.

“The Mexican American isn’t seen as being as profitable, man,” he says, revealing an undercurrent of tension between the two groups. “The immigrant is more profitable.”

That hasn’t stopped him from trying to resurrect the dream of a Mexican American Motown, re-releasing classic albums, making the music digitally available in scores of countries and signing new acts.

He knows it won’t be easy. But he believes it’s his destiny.

“I figured I’m going to try to be the guy, even if I end up homeless.”

::

Gonzalez is sitting in his Rampart Records office in a squat stucco cottage in Santa Fe Springs, across the street from a gentleman’s club and conjoined to a smog-testing business.

It’s a cave of an office, about the size of a cruise ship cabin, packed with vintage Vox amplifiers, recording equipment, vinyl albums, master tapes and promotional material from the ’60s and ’70s, and random toys like the monster from Ridley Scott’s sci-fi classic “Alien.” A promotional pamphlet Davis conjured up in 1970 proclaims: “The Sound of a New Generation, Chicanos are Happening!”

The office doubles as his home, with a fridge and a sink. In a back room, an over sized guitar — or guitarron — hangs over his bed, along with a poster of Robert De Niro from “Taxi Driver” and a painting of the Virgin Mary holding the baby Jesus. He likes to work on his music at night, when the noise outside on Norwalk Boulevard ebbs.

Nothing in the office suggests that a would-be music mogul occupies it except Gonzalez’s energy. Stocky, with a robust mustache and a baseball cap, Gonzalez drives a pale olive green ’65 Thunderbird with a rust-marbled top and talks in fast superlatives.

“My whole thing was to keep the legacy and the voice of the Mexican American going,” he says. “The musical voice of us.”

Gonzalez is telling the story of how he met Davis, a music impresario who was a former child actor turned restaurant owner. Davis had started his career as a music mogul in the late 1950s, producing both black and white artists. As a child his family moved to Boyle Heights, and by the early 1960s, he was a committed producer of Mexican American rock.

It was a good time to do this. Ritchie Valens had inspired many young Mexican Americans, and elsewhere, other Mexican American acts were making their mark, including Michigan’s Question Mark and the Mysterians (“96 Tears”) and Sam the Sham and the Pharaohs (“Wooly Bully”).

Gonzalez had never heard of Davis while growing up in South L.A. and then Bell. But after starting a soul band with some friends, he began to ask older musicians for advice on breaking out, and they told him to go find Eddie Davis. He tried, but it wasn’t easy.

“I went through the Yellow Pages. It was impossible to find him,” Gonzalez says. “Finally, I found him. He was under Record Manufacturer. He had an office in Hollywood.”

http://www.crnlive.com/CRNBlog/index.php/2013/01/eastside-record-label-still-spinning-out-the-music/ |